A Message from the Ordinand

By Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber

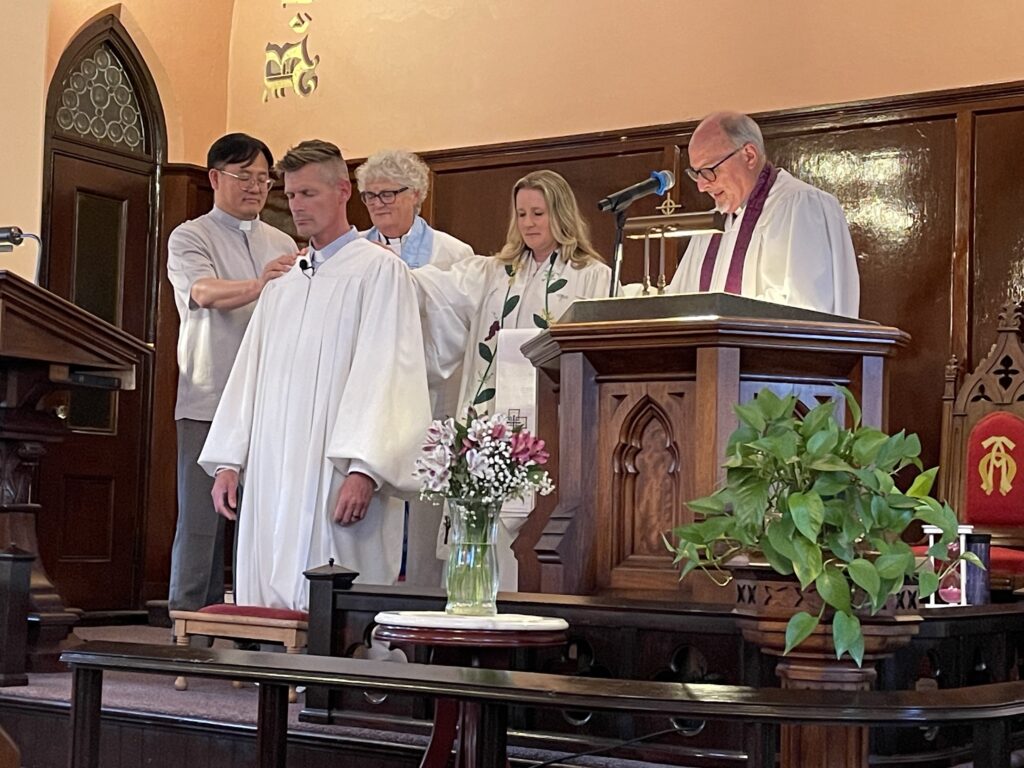

Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber delivers his message.

The text for my sermon today comes from the gospel of Mark 4: 26–32:

He also said, “This is what the kingdom of God is like. A man scatters seed on the ground. Night and day, whether he sleeps or gets up, the seed sprouts and grows, though he does not know how. All by itself the soil produces grain—first the stalk, then the head, then the full kernel in the head. As soon as the grain is ripe, he puts the sickle to it, because the harvest has come.” Again he said, “What shall we say the kingdom of God is like, or what parable shall we use to describe it? It is like a mustard seed, which is the smallest of all seeds on earth. Yet when planted, it grows and becomes the largest of all garden plants, with such big branches that the birds can perch in its shade.”

On my long flight from San Francisco to Boston, I had a window seat. Back In the San Francisco Bay, I was leaving behind one of the coldest, wettest, and grayest June gloom summers we’ve ever had – it’s been San Francisco’s consistently coldest summer on record since 1911. Strange weather for us Californians, to lurch into one of the coldest wettest seasons, after decades of a parching mega-drought. As my plane approached the Midwest, I began to take note of a pale, sickly haze, a film that obscured the white clouds further below, and then I realized, of course, that I was looking down on the giant plume of smoke from the Canadian wildfires: arboreal forests, the largest single intact forest ecosystem in the world, was being incinerated somewhere down there, millions of acres of trees transmuted into ash in the sky. I’m sure many of you went through some level of this on your journeys to get here. What a way to look at the earth, this ashy lens of tree death that reminds us it is, indeed, a small world after all.

As the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg has put it, we are living through “Code Red” from the planet—our earth systems are out of alignment, destabilizing like a spinning top that gyrates and spirals out of control in increasingly dramatic extremes of weather. The uncertainty we find on the earth seems to mirror the fragility of our fraying democratic systems—unsettling cracks in governance, failures of equity and accountability, a general unbalancing and polarization. Left here, Right over there, and pundits speak ominously about the undertow of a so-called “slow civil war.” At a similar prior moment of turbulent history in the early twentieth century, the great Irish poet William Butler Yeats—who himself was a deep reader of Swedenborg—described this sense of unraveling, of centrifugal forces pulling cultural cohesion apart, in the following well-known lines from his poem, the “Second Coming,” which was written in the turmoil and aftermath of both the first World War, and Ireland’s own bloody struggle for independence:

Rev. Junchol Lee helps Devin get prepared.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

As our climate turns and turns in widening gyres, extremes of temperature and weather, how are we to find hope? How do we as Christians, as Swedenborgians who believe in the coming of a better world, engage with the Practice of Optimism—the theme for this year’s Convention—when our natural and political orders seem to be in such depressing disarray and deep disfunction? The best lack all conviction, the worst are full of passionate intensity.

It is the deepest honor and privilege to stand here tonight in Bridgewater, not as an academic or a scholar of Swedenborg, but as someone who joins the ranks with my brothers and sisters in the service of ministry and usefulness to this church. A cloud of witnesses stands behind me that has brought me to this point—parents, grandparents—and I wonder about the line that goes further back for everyone like me who has felt a call to the ministry, a lineage that begins in the oldest of the Gospels, Mark, at the very end, after Jesus has returned from the dead and miraculously appeared–firstly, to the women!—and then to the eleven male disciples. The Great Commission is then given, and any minister within all the varieties of Christianity over the centuries has had to grapple accordingly with what it means to heed this final commandment from the Lord: We are to go into all of the world, and preach the Good News to the whole of Creation.

Perhaps this is the original instance of a Christian practice of optimism, as a spiritual discipline—to give Good News to the whole of Creation, not in spite of the world’s brokenness, but because of it. The Good News is a message of freeing transformation, that things do not have be the way they are, that we do not have to be in a state of despair, mired in what Swedenborg would call the delusions of hell. If we believe, and receive the influx of the Divine into our hearts and minds, we – and the world around us – can be accordingly redeemed.

And isn’t it interesting that this command for the gospel, this good news of salvation, is not just a message to be preached to our fellow humans, but to all of creation? The Greek word for all of creation in the biblical text here is ktisis (κτίσις) – it means a creation that has been made by a Creator, a capacious term that is importantly, critically, not limited to humans, and can be read as entailing all of the creation and its various creatures. When I hear or read this Great Commission—to preach the good news to the whole of Creation– I often think of the that wonderful medieval saint, Francis of Assisi, who in the thirteenth century preached this message to the birds in the trees. St. Francis said:

“My sweet little sisters, birds of the sky, you are bound to heaven, to God, your Creator. In every beat of your wings and every note of your songs, praise him! He has given you the greatest of gifts, the freedom of the air. You neither sow, nor reap, yet God provides for you the most delicious food, rivers, and lakes to quench your thirst, mountains, and valleys for your home, tall trees to build your nests in, and the most beautiful clothing: a change of feathers with every season. please beware, my little sisters of the sky, of the sin of ingratitude, and always sing your praise to God.”

A practice of optimism from the Gospel of Mark onwards is grounded in turning to the Creation. Can you also, like St. Francis’s birds, voice praises of gratitude to God for food, rivers, and lakes, as effortlessly as the bird song which has filled our evening sky of this fine New England summer evening? Perhaps bird song is a kind of hope; in Swedenborg’s system of correspondences, birds represent “matters pertaining to the intellect,” which while at first hearing sounds quite dry and clinical, actually beautifully connects the flights and perches of our various trains of thought with these glorious winged creatures of the air. That great nineteenth century poet and female theologian from Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson, meditates deeply on the relation between birds and the practice of optimism in her poem, no. 254:

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune without the words,

And never stops at all,

And sweetest in the gale is heard;

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little bird

That kept so many warm.

I’ve heard it in the chillest land,

And on the strangest sea;

Yet, never, in extremity,

It asked a crumb of me.

The gospels are filled with an earthy turn towards creatures and creatureliness, grounded in the abundance and goodness of the planet. The kingdom of heaven, again and again, is described by Jesus as seeds and seedtime, the little mustard that becomes the largest of all garden plants, with shade for the singing birds; seeds that flourish and grow independent of human control: “Night and day, whether he sleeps or gets up, the seed sprouts and grows, though he does not know how. All by itself the soil produces grain.”

This well-worn parable, but one that never gets old, acquired new meaning for me this past spring when I traveled to Palestine with the Center for Swedenborgian Studies, accompanying students, and various members of our board and community. We traveled together up to the Sea of Galilee, and stayed in a Franciscan convent on the Mount of Beatitudes, reputedly the site where Jesus taught on the hillside, and delivered the teachings that came to be known as the Sermon on the Mount. The mountains and valleys around the shining lake where Jesus had lived and walked and preached were incandescent with wildflowers, and fragrant with blooming trees. As well as shrieking green parrots. We traveled northwards into the Golan Heights where the water from Mt. Hermon—the dews of Mt. Hermon—flowed furiously down towards the Sea of Galilee, a bucolic, almost impossibly beautiful landscape, until one looked closer, and began to realize that behind the fields of yellow and red flower — poppies, anemones, and cyclamen—there were tangles of barbed wire, fencing with razors of concertina. My desire to run off and explore these flowered expanses was immediately tempered by the rusty yellow signs we began noticing, everywhere, which warned us of active land mines. In our bus, we passed bombed-out and abandoned buildings between the green, the shell of a burnt out car on the side of the road—remnants of a still active conflict between different groups and nations in a lethal territorial dispute. And still, there, spring after spring, these flowers in the Golan Heights return and bloom, impossibly, in a landscape scarred by trauma and violence.

Part of our time in the Holy Land was spent staying in the homes of Palestinian families, who generously fed and housed us for a night. I stayed with one family of woodworkers outside of Bethlehem, along with my now fellow minister Dan Burchett. The family was very proud to tell us how in a way they were truly the oldest Christians in the world, descended from the same stock of people who had first heard the good news of Christ’s birth when the angels appeared in a blaze of glory to the shepherds outside of Bethlehem, keeping watch over their flocks by night. But, thirty years ago, in that house where Dan and I slept, where the family had been consecutively living for generations, the Israeli authorities came in and completely destroyed the family home with bulldozers, razing it to the ground. They lost everything, and had to rebuild the entire structure, story by story. Over dinner Dan and I asked the family how, then, in spite of all of this tragedy, did they still manage to have hope?

The family immediately, all of them, burst out into laughter at this question. They found it hilarious, once it had been translated, these two naïve white American guys, asking about hope – the older parents clarified to us – “Hope? We do not have hope. How can we? The situation is so absurd.” Though their laughter first surprised and chastened me, I later realized that while they may not have a cheap sense of hope—a false belief that somehow the current apartheid system in Israel, so rigged against them and denying them of basic rights, could ever deliver them any measure of justice—this family nevertheless had a fiercely beautiful, daily practice of optimism. In their back yard, they proudly showed us the only thing the Israeli bulldozers had not destroyed: an ancient gnarled olive tree, at least four hundred years old, which still produced olives, which they continue to make olive oil out of every year. Who knows how many of their grandfathers and great grandmothers and beyond had touched and pruned, water and harvested the fruit of this very tree, which we tasted in the olive oil used in the food that they prepared for us that evening. The tree was still there, with its leaves—leaves for the healing of the nations, and with ample branches for the singing birds.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that our little church tradition takes its cues from the theological writings of someone who was not just a scientist and a mystic, but a grubby gardener who got his hands dirty in the soil, and loved tending to his vegetables and flowers, lemon and mulberry trees, and kept a large cage of singing birds in his garden. As a church, in general, we do not make enough of this fact. As any of you here who are gardeners know, to garden is inherently a practice of optimism – a hope and faith in a future flowering, a patience tempered by frustrations and failures, and always anticipating the unexpected and unpredictable. It also requires a letting go. Recall the gospel again: “Night and day, whether he sleeps or gets up, the seed sprouts and grows, though he does not know how. All by itself the soil produces grain.” In Swedenborg’s book, Divine Love and Wisdom—one of his theological works that is engraved with the image of an angel watering a bed of flowers, under a banner that reads CURA ET LABORE, “with loving care and effort”—Swedenborg euphorically describes the interconnectedness of all the things in the natural and spiritual worlds. He describes the forms and species of nature, propelling upwards into one another. Minerals aspire to be plants, and in all of plant life, Swedenborg says, “there is an energy towards movement” that approximates animal, and then human, life. “There is a ladder in all created things,” the text goes, an interconnectedness which should “stun” our minds with amazement and wonder.

The practice of optimism in our moment of planetary emergency perhaps requires less rational plans for the future—less abstractions of facts and statistics about carbon emissions—and more cultivation of how we can attune ourselves to feeling the wonder and awe of the creation with our five senses, in this gift of our perceiving bodies: eyes and ears, touch, taste, and smell. When is the last time that you have been stunned by this interconnectedness, the ladder in all created things? When have you tasted and seen that the Lord is good?

Post COVID, still in our brave new world so heavily mediated by Zooms and constant screen-time, and the incessant distractions of so-called smart phones, we would be wise to heed the words of the Psalmist from 2,500 years ago. This is from Psalm 8:

O LORD, our Lord,

How excellent is Your name in all the earth,

Who have set Your glory above the heavens!

When I consider Your heavens, the work of Your fingers,

The moon and the stars, which You have ordained,

What is man that You are mindful of him,

And the son of man that You visit him?

In closing, It is my hope and sincerest prayer for you in the summer months remaining, that we can all find adequate time to be still; to be quiet in the ways which open us to getting stunned with wonder, and to practice the corresponding gratitude and optimism which flows from these moments when we are able to find heaven in wildflowers, and in the singing of the birds.

Read the full issue of the Convention Special 2023 Messenger

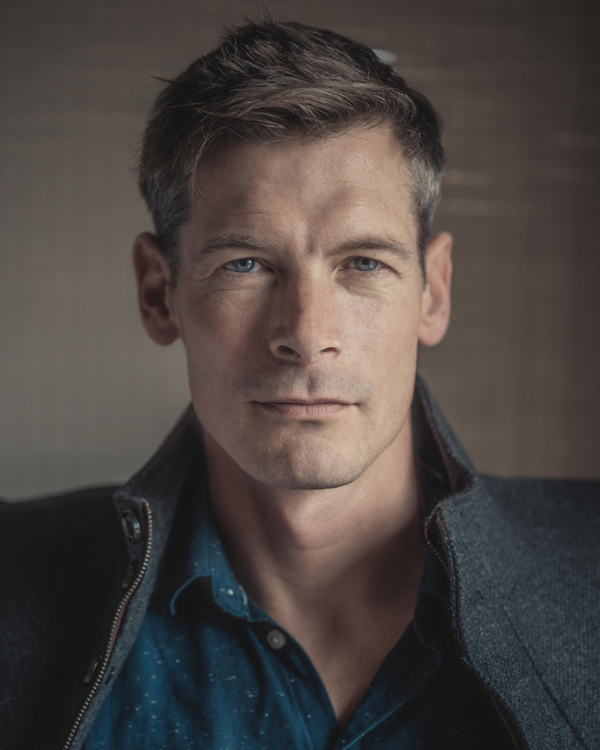

Meet Devin Zuber

Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber is the George F. Dole Professor of Swedenborgian Studies at CSS in Berkeley, California, where he also serves at the Graduate Theological Union as chair for the Department of Historical and Cultural Studies. He has published widely on art, literature, and Swedenborg’s influence on the nineteenth-century. Before moving to California, Devin taught at universities in Germany, and has held fellowships or visiting professorships at the British Library, Stockholm University’s Department for Aesthetics and Culture, and the Rachel Carson Center for the Environment (LMU Munich). He also serves the Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco as a ministerial assistant.