Notable Swedenborgians

Swedenborgianism has attracted many notable people since its inception in the early 19th century.

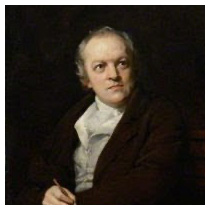

William Blake

Poet & Artist, (1757-1827)

An early reader of Swedenborg, Blake was present at the first conference of the New Jerusalem Church held at Great East Cheap in the City of London in April 1789. Although he did not stay with the organization and was fiercely critical of Swedenborg in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-1793), Blake was to praise Swedenborg on later occasions and acknowledge his influence, calling him a ‘divine teacher’ in a conversation in 1825 recorded by Henry Crabb Robinson. The influence of Swedenborg’s teachings may be found in many places in his poetry, prose and visual art.

Charles Bonney

Attorney, Judge, author, and founding member of the Parliament of World Religions, (1831 – 1903)

Born in New York, Charles Bonney was a lawyer and, later, a judge for the Supreme Court of Illinois. He was also active in organizing the Parliament of World Religions in 1893. During the World Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) in Chicago, there were so many people traveling to the region that several smaller groups of religions decided to hold their meetings there. Charles Bonney came up with the initiative to have a single large gathering representing all of them. This is considered the first organized interfaith gathering. Represented was Jainism, Buddhism, Zen, Hindu, Christianity, Islam, and Theism among others.

Daniel Burnham

Architect, (1846-1912)

Daniel Burnham, a renowned Chicago architect, was a pioneer in both skyscraper design and city planning. A lifelong Swedenborgian (and grandson of a Swedenborgian minister) he attended Swedenborgian schools as a boy and teenager.

After completing an architecture apprenticeship, he joined a firm and met fellow trainee John W. Root, who shared Burnham’s enthusiasm for Swedenborgian ideas. They formed Burnam and Root, which became the leading architectural firm in Chicago. The firm was responsible for some of the most admired buildings of the renowned Chicago school, among them the Monadnock Building and Masonic Temple. After Root’s death in 1891, Burnham designed the famous Flatiron Building, New York’s’ first skyscraper, and Union Station in Washington, D.C.

It was in the realm of city planning, however, that Burnham realized his greatest and most enduring achievements and it is there that the inspiration of Swedenborgian ideas is most profoundly embedded. Burnham supervised construction of the great Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, creating the “White City” as an ideal model for a modern city. His work—which strived to realize Swedenborg’s heavenly city in stone, steel and concrete—has shaped much of 20th century America’s urban landscape.

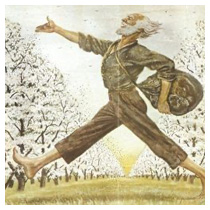

John Chapman

American Folk Legend, (1774-1845)

John Chapman is the real name of American folk hero, Johnny Appleseed. Johnny Appleseed is best known for planting and selling apple trees throughout Ohio and Western Pennsylvania, while living his life as a nomad. He is known for being gentle and giving, wishing for settlers to have his trees to plant, even if they had no means to purchase them. He was also a Swedenborgian missionary. Everywhere he roamed he would give people pieces of Swedenborg’s theological writings that would get passed around, almost as a kind of lending library.

To learn more about Johnny Appleseed, consider a visit to the Johnny Appleseed Educational Center and Museum.

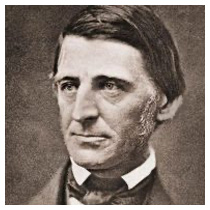

Ralph Waldo Emerson

American poet, philosopher and essayist, (1803-1882)

The American poet, philosopher and essayist first encountered the works of Swedenborg while he was a student at the Harvard Divinity School and remained a keen reader throughout his life. His biographical essay, ‘Swedenborg, or the Mystic’ was published in his Representative Men (1850). References are made to Swedenborg in several other works, including English Traits (1856) and the poem ‘Solution’ in May-Day and Other Poems (1867). Emerson wrote of Swedenborg: “A colossal soul, he lies vast abroad on his times, uncomprehended by them, and requires a long focal distance to be seen.” Emerson’s embrace of Swedenborg encouraged other transcendentalists, among them Margaret Fuller (1810–50), a journalist and early leader in the women’s rights movement.

Helen Keller

Inspirational Speaker and Author, (1880-1968)

The story of Helen Keller is one of the most inspiring of our times. Blind and deaf from the age of 19 months, she was wild and unruly in her childhood. The devoted efforts of her teacher Anne Sullivan opened the world to her and gave her the capacity to develop and express her extraordinary intelligence. In defiance of tremendous odds, she learned to read, write, type, and speak, and in 1904 she graduated with honors from Radcliffe College.

Keller was introduced to the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg by John Hitz, a longtime friend who was a member of the Church of the Holy City in Washington, D.C. As she began to read Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell, she remarked, “my heart gave a joyous leap.” She went on to write, in My Religion, of the spiritual odyssey that brought her to Swedenborgianism and endowed her with the inner resources to triumph over her handicaps and live a life of selfless service.

She remained a devoted member of the Church of the Holy City and on one occasion preached from its pulpit. Her extensive study of Swedenborg’s works gave her the sustaining power of faith that energized and shone through the great work of her life.

Dr. Kristine Mann

Physician and Analytical Psychologist who co-founded the Jungian Institute, (1873–1945)

Dr. Kristine Mann, daughter of Swedenborgian minister Rev. Charles Mann, devoted her life’s work to women’s health and Jungian analytical psychology. From 1920-1922, Mann and Eleanor Bertine traveled to London and Zürich, to study under Carl Jung. When they returned to New York, they established their own practices, becoming the second and third Jungians to treat patients in the United States. Kristine Mann, Mary Ester Harding, and Eleanor Bertine spent summers at Mann’s ancestral summer community at Bailey Island (Maine) where they established their practices in the summer and saw patients from all parts of the United States.

In 1936, Jung traveled to Bailey Island to present his Bailey Island Seminar, the first of his two-part American seminar Dream Symbols. The second part—known as his New York Seminar—was held in New York one year later in Mann’s apartment. The seminars were published in volume 12 of Jung’s Collected Works as Individual Dream Symbolism in Relation to Alchemy.

The three female doctors were a powerful trio. They created the Analytical Psychology Club of New York and actively led the club’s educational programs there. At her death in 1945, Mann left her personal library to the club, which led to the formation of the Kristine Mann Library that is now the most extensive collection in analytical psychology in the world.

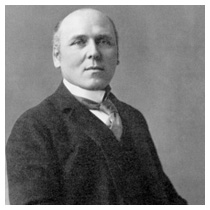

Howard Pyle

Author and Illustrator, (1853 – 1911)

From Wilmington, Delaware, Howard Pyle was an American author and illustrator of primarily children’s books. He also started his own school of art and illustration named the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art in Pennsylvania. His most famous publication is, “The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood,” which is still in print, and he is responsible for much of the modern understanding of the Robin Hood myth. His drawings of pirates have been credited with what we consider to be the stereotype of pirate dress.

It is said that he would have his secretary read Swedenborg to him while he painted. In an article printed in the Mercer Sun-Star on November 8, 1894, it notes that he is a, “man of peace, for to his inherited Quakerism he has added a personal acceptance of the faith taught by Emmanuel Swedenborg.”

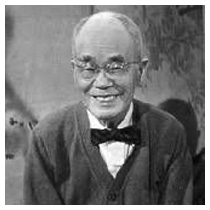

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki

Zen Buddhist Scholar and author (1870-1966)

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki was an internationally known Japanese Zen Buddhist scholar. He lived in the USA from 1897 to 1908 where he met his wife, Beatrice Lane (who had studied under William James, among others). It may have been through her that he first encountered Swedenborg’s works. He translated Heaven and Hell, The New Jerusalem and its Heavenly Doctrine, Divine Love and Wisdom, and Divine Providence into Japanese. He was Vice President of the 1910 International Swedenborg Congress and wrote a long essay on Swedenborg, Suedenborugu. He described him as, “the Buddha of the North.”

Eliza Lovell Tibbets

Early American activist, (1823-1898)

California’s citrus industry owes a huge debt to the introduction of the navel orange tree—in fact, to two trees in particular, the parent trees of the vast groves of navel oranges that exist in California today. Those trees were planted by a woman named Eliza Lovell Tibbets.

Born in Cincinnati in 1823, Eliza’s Swedenborgian faith informed her ideals. Surrounded by artists and free thinkers, her personal journey took her first to New York City, then south to create a better environment for newly freed slaves in racially divided Virginia. She went onward to Washington, D.C., where she campaigned for women’s rights. But it was in California where she left her true mark, launching an agricultural boom that changed the course of California’s history.

Eliza’s story of faith and idealism will appeal to anyone who is curious about U.S. history, women’s rights, abolitionism, spiritualism, and California’s early pioneer days. Follow Eliza through loves and fortunes lost and found until she finally finds her paradise in a little town called Riverside.

Reference: Creating an Orange Utopia: Eliza Lovell Tibbets and the Birth of California’s Citrus Industry by Patricia Ortlieb and Peter Economy, Swedenborg Foundation, 2011

“Of all the unconventional current streaming through the many levels of American religion, none proved attractive to more diverse types of dissenters from established denominations than those which stemmed from Emanuel Swedenborg. His influence was seen everywhere…”

-Sydney Ahlstrom, Yale Church History Professor