Written by Rebecca Esterson

Many of us travelled a long way to be at Convention this year. We came by train, bus, and car. On the other hand, many of us travelled shorter distances to be with the community virtually, having travelled from the kitchen to the living room, or from the living room to the back porch. All of us, however, made a journey of intention, in spirit, to be present for this time, to be together. These are troubled and troubling times, and it is important to be together to find fellowship and perspective. What a blessing!

I drove to Convention, from Northern to Southern California, with my fellow pilgrims Debbie and Dru, and we had an enjoyable trip. Along the way we enjoyed three of my favorite things: beautiful scenery, good conversation, and plenty of coffee. But another reason I was grateful for the drive involves something of a confession: I have a terrible fear of flying. Like most phobias, it isn’t a rational fear and there’s really nothing anyone can tell me, or anything I can tell myself, about the safety of air travel that will lessen my fear. I experience it as a physical reaction, as though it were written into the code of my DNA. As soon as the wheels of the plane take off, I go into a panic. I sweat, my heart rate rises, I look around in confusion at the other passengers and the flight crew, none of whom seem to share my sense of acute danger and wonder at how our experiences of flight can be so different. But I can’t think myself out of it. It is though my body has a kind of consciousness of its own, a firm and stubborn belief that it belongs on the ground, no matter what my brain tells it. As far as my body is concerned, the sky is a place of death and danger, the ground is the place of life and stability, peace and sanctity. When I land, I want to press my forehead against the ground and thank the Lord for the steady earth. My fear of flying is not logical, and it has been the source of significant obstacles. But it has also provided occasions of insight, or at least a particular vantage point from which to contemplate being and existence.

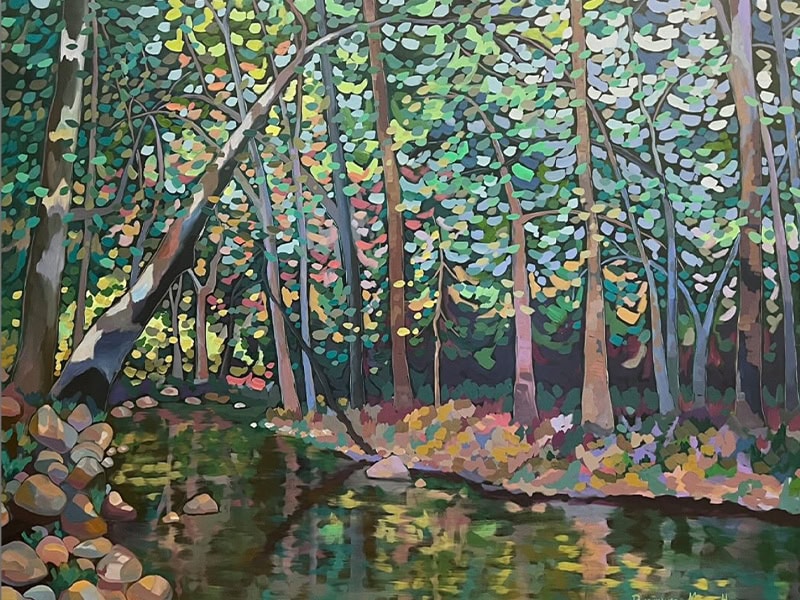

While many who count themselves among the spiritually oriented might look to the sky, the air or the stars, for inspiration, I look to the earth. I look out and down and wonder at the weight of our bodies against the face of this earth. There is belonging here with the creeping things, the flowing water, the majestic landscapes. My greatest experiences of gratitude and awe come, not from gazing into space, but from experiences of groundedness. Earth is where I want to be. I am only half-joking when I tell my kids space travel is the one profession that I forbid them to consider.

As Swedenborgians, we tend to view the sun as a model for Divinity, the one true source of light and heat, love and wisdom from above. Swedenborg describes the sun in heaven as the aura, or emanation of God, and the sun of our world as the emanation of that sun. The sun often features, therefore, in our metaphors for Divinity, its relationship to the moon, the clouds, the planets, figure in our theological models for the interplay of forms of truth and love. However, for our time together this evening, I wonder if you might engage me in a thought experiment suggested by this attraction to the earth that my fear of flying has encouraged. In what ways might the earth correspond to God? What do her features and forces tell us about divinity, or about forms of love and wisdom?

Whether or not you share my preference for earth over sky, I invite you to a reflection on what it means that we are tethered this way. I invite you to pause for a moment and notice how the weight of your body is held by the earth. We are conditioned to think of our weight as a troubling feature, something to be assessed and resisted, lightened by sheer force of will, as though we could shake if off and fly free. Let go of those conceptions for a moment and imagine that your attraction to surface of our planet is a gift of belonging. You belong here in the fullness of your weight, alongside the trees that sway and the animals that run. Feel the weight of your form grounding you. Now notice the chair that you sit on, or the floor below you, which pulls and hugs. Look down and notice it’s color and texture. Imagine what might be just below the floor, perhaps another room is down there, a basement filled with things for another day. Go deeper still, in your imagination, through the boards, concrete, wires and pipes and visualize yourself in the earth, with the soil. Imagine being able to see the incredible energy of the soil, the magical process of decaying bodies of plants and animals being reformed into nutrients which infuse the soil with vitality and potential. As you go into the earth you might encounter created beings still living, root systems and wiggling forms. The crust of our planet is about twenty miles deep, on average, but no human has ever seen more than 8 miles down. We can study lower layers of our planet through the patterns of seismic waves and speculate about the contents of what lies below, though much mystery remains. Such studies suggest that below this thin layer of earth and ocean, this crust, there is a large mass of material called the mantle which extends another 18 hundred miles down. As we move through the mantle we encounter mostly solid rock, some layers burning hot, some layers icy cold. There are also layers that are more fluid, which allow for the movement of the tectonic plates above, bearing our land and our seas. If we were to go further still we would encounter what scientists call the outer core and the inner core of the earth. Here the temperature reaches that of the sun, about 10k degrees F. So that, astonishingly, while surface creatures soak up the sun’s rays above, there is another parallel source of heat under their feet. The inner core, the ball at the center, is a little smaller than the size of the moon, and is a solid mass of mostly iron. It is heated well beyond melting point but lies under so much pressure that scientists believe is must be formed into solid crystals, or a single crystal, floating there in the middle and rotating at its own pace, distinct from the rotation patterns of the earth as a whole. The outer core, on the other hand, which surrounds this iron ball, is not solid, but a liquid formed of heated metals, its movements fluid and flowing. Like the tides of the oceans on the earth’s surface, the liquid metals in the outer core are pulled by the gravitational forces of our moon, and experience tides (there are fluid tides in the center of the earth). These “Earth tides” as they are called, create our planet’s electric currents which are responsible for the geomagnetic field. This field, which gives our planet its magnetic poles, radiates from the core out into space where it meets the sun’s energy and protects our atmosphere from powerful solar winds. These tides, these currents, these magnetic energies are what allow our planet to form a protective ozone layer, giving us the movements of air and water in which we live and thrive in an ecosystem of unimaginable beauty and diversity. So that as we sit and stand here presently, we have all of this below us and around us, a gift of energy and space and life.

All of this, of course, is temporary. Our planet was born about four and a half billion years ago, they say, and in the blink of an eye, in another four and a half billion years by some estimates, after the water has vaporized and the magnetosphere of our planet decays, our sun will die out and whatever remains of earth will be set adrift.

But here is the great and holy paradox that our tradition, in the wisdom of our ancestors, teaches us: while this planet may be temporary, it nevertheless contains the infinite because it contains life. There is eternity here, in our weighty bodies, and in the bodies of every created thing that walks on the shell-surface of planet Earth. We are born and we die, but we are also eternal and infinite. And this isn’t simply a teaching about the afterlife. Our planet contains the infinite and eternal right here and right now among the living. How can this be?

In his genre-defying book The Worship and Love of God, Swedenborg retells the creation story of the cosmos in terms scientific, poetic and deeply devout. In it, he imagines our planet earth at precisely the stage between its formation and the emergence of life on its surface. Having solidified into a mass of particles that spiraled out from the sun, a crust has formed on its surface, like an eggshell. Scattered on this shell he imagines seeds of every living creature, plant and animal, the potential for infinite varieties of life lying in wait. And in this pregnant moment, he writes, the earth contained eternity within it, time stretching backwards and forwards indefinitely. “Thus the present contained the past, and what was to come lay concealed in each [seed], for one thing involved another in a continual series; by which means this earth, from its continued beginnings, was perpetually in a kind of birth, and, as it were, looking to that which was to follow; while it was also in the end, and, as it were, forgetful of what was gone before” (Worship and Love of God §15). It is as if new forms of time and space, infinity and eternity, were born in a single moment on the surface of our planet because of this potential for life.

In the works Divine Love and Wisdom and Divine Providence, this theme of eternity in the pregnant present is explored theologically. We read that there are two core features of the Divine, one contained within the other like our planet’s inner and outer core. Divine Love at the center and Divine Wisdom surrounding it, constitute the very essence of God, and these are reflected in the two related qualities of infinity and eternity. We read in Divine Providence §48: “What is intrinsically infinite and intrinsically eternal is the same as Divinity.”

Of these two, infinity (which concerns space) and eternity (which concerns time), let us consider infinity first.

Swedenborg writes that we see an image of the infinite in the variety of everything created. Even within a given species, no created thing is like any other created thing, however much they reproduce. He uses the example of fish, and suggests we imagine that a given species of fish were to reproduce to its fullest capacity for a hundred years. They would surely fill the universe, he writes, and still no two would be exactly alike. Their variety can never be exhausted or even diminished. Variety in creation is truly infinite. This is true also of the human face, which, we read, is uniquely suited to figuring the infinity of the Divine. The variety of forms and expressions in the human face are themselves like a mirror, reflecting the infinite variety in God’s own face. “We can see an image of what is infinite and eternal in the variety of everything in the fact that nothing is exactly like anything else, and nothing can be to eternity. We can see this in the faces of all the people there have been since the beginning of creation, and from their characters as well, which are reflected in their faces” (Divine Providence §56).

This leads us to a consideration of eternity. If we were to pluck one fish from our universe of fish, she would contain within her the property of eternity, simply by the fact of her having come from her parent fish who came from their parent fish back through the generations and evolutions, and by the fact of her having the capacity to reproduce infinite numbers of generations into the future. Whether or not she lives to produce offspring, her body will go on to replenish her native habitat with nutrients and she will supply future generations of diverse species with the capacity for life. She is herself an image of the eternal, stretching backward and forward in time. This week at Convention we will have the opportunity to visit the Garden Church in San Pedro (a church that’s a garden, a garden that’s a church). While there you might enjoy images of eternity in a number of ways. You might see their composting bins, where death passes into life, decay transforms into fertilizer, realizing right there the promise of eternal life. And if you pick up and hold just one seed from the garden you will have in your hand a container for and image of the divine, infinite and eternal, entirely unique and also entirely interconnected.

The planet, or the garden, which is a microcosm of the planet, tells us something about the nature of Divinity and the nature of our inner being. All of these forms of infinity and eternity in the natural world around us are also present in the forms of love and wisdom within us from God. Our loves and wisdom, like the Divine Love and Wisdom of our source, are both infinite (in variety) and eternal (in that they can bear fruit endlessly). Swedenborg writes that this applies to every element of our desires, perceptions, and ideas. Our inner world is like the fish of the sea, or the seeds in a garden: totally unique, beautiful, and holy to the core. There is nothing we can do to remove this quality of the divine from within us. We are as diverse interiorly as the species of our planet. When we behold the beauty and variety of our world, we are, in a sense, looking in a mirror, “The fact that the universe consists of constant useful functions produced by wisdom under love’s initiative is something all wise people can contemplate as if they were seeing it in a mirror” (True Christianity §47).

This has implications for how we understand the oneness of God. We read in Divine Love and Wisdom §155 “diversity arises from the fact that there are infinite things in the Divine-Human One.” God is One, but God is not one thing. God is one, but infinitely so, containing infinite things. And creation is the expression of this infinite oneness. The diversity expressed here on the surface of our planet is the embodiment and incarnation of God, the image of God, what Swedenborg calls the “distinguishable oneness” of the Divine.

But our reverie is interrupted. This thought experiment considering how earth corresponds to Divinity stops at the inevitable point when we acknowledge that our planet is not always so beautiful. How can this planet be a model for the Divine, you might ask, when it also witnesses the annihilation of diversity, war and decay, ecological disaster, hatred, destructive greed, violence, and suffering? All of this is also permitted by the dynamic interplay of gravitational and magnetic forces that give our atmosphere its stability. Evil lurks under our precious ozone. We are provided life by precisely those forces that our life goes on to destroy. Can this also be the image of God? These are the questions raised by such radical immanentism, and these are the questions raised by the urgencies of our time.

The French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas is a helpful interlocutor when considering these kinds of questions, questions about the brutality of our world, and questions about infinity and encounter.

Levinas lived through the atrocities of the second World War, as a Jew and as an enlisted member of the French army. He witnessed human nature in its most destructive forms. Though he survived, held as prisoner of war, many of his family members were brutally murdered by Nazis, and for the remainder of his lifetime, his work as a philosopher and Jewish educator would be deeply informed by this encounter with extreme malevolence. In his magnum opus, Totality and Infinity he reflects on the effects of war in suspending morality, that war dupes us into a misguided sense of our own moral advantage, or the moral advantage of people with whom we identify. Both sides in a war such as the one he survived see themselves as guided by ethical intentions, yet, ironically, war has the effect of destroying our very ability to act independently as moral agents. Instead, we are compelled to act for the sake of some totalizing framework. Key to what he calls this “totality” is valuing what is the Same over and above what is Other, what is different. Totality values of sameness. Totality, Levinas will argue, is not just a problem of wartime, but is at the heart of a fundamentally flawed way of conceiving of Self and Other that characterizes Western thought. All of Western philosophy, Levinas argues, has misled us into centering our epistemologies around knowing the Self. Our relationships to other beings, in this perspective, are framed according to how much we recognize ourselves in other beings and other things. Successful relationships, according to this view, successful reasoning, successful living, all depend on knowing the self. Such a perspective finds happiness in recognizing ourselves in other people and in seeking to be with people who are like us, it values sameness over difference, at any cost.

Levinas suggests a reverse perspective, a phenomenology of exteriority, in which we sacrifice the need for sameness for the value of otherness. He suggests that we only come to know ourselves through our encounter with the otherness of Others, and that the encounter with something entirely outside of ourselves, the absolutely Other, is revelatory. The truth is revealed to us through the encounter with the Other. And while totality is the end goal of war, relationality is the only thing that can restore peace.

Here is where he brings in the concept of infinity. Infinity is the opposite of totality. When we encounter the otherness of the Other, the foreignness of the face of someone different from us, for instance, we encounter the infinite, the beyond, the whole. When we see the face of the Other as absolutely Other, rather than seeing them as a version of ourselves, we see infinity. This kind encounter, and no other, invokes responsibility for the Other, our neighbor, and compels us to ethical action.

Swedenborg puts it this way: “Feeling the joy of someone else as joy within ourselves—that is loving. Feeling our joy in others, though, and not theirs in ourselves is not loving. That is loving ourselves, while the former is loving our neighbor. These two kinds of love are exact opposites” (Divine Love and Wisdom §47).

In other words, if we only want for other people what brings us joy, we don’t really love them or want what’s best for them, and we will not act in their best interests, but ours. We must cultivate a love that decenters the self, decenters the familiar, that can expand to include forms of joy, ways of being, that are different from what we already know.

Issues of otherness and totality carried specific cultural and political implications in the middle decades of the twentieth century, when powerful forces worked to eliminate racial or ethnic difference through genocide, eugenics, segregation, and other means. But they are no less relevant today, not only in the ways the effects of these events persist, but also in new forms of polarization. Many of us experience extreme forms of totality in our discourses today. We are divided into camps of like-minded people who have become skilled at villainizing the other rather than seeing the wellbeing of the Other as our moral responsibility.

Here is where looking earthward for models of Divinity might benefit us. Ours is a moment that requires an eternal and expansive God. A God that is an ecosystem of infinitely diverse elements. A living God. A God in whom there is vitality, multiplicity, difference. Swedenborg writes, “Every one [unum] is formed from the harmony of many; and the one is such as the harmony is; nor can there ever be an absolute one, but only a harmonic one.” God is the Harmonic One. And we encounter God in the full range of the chords, the full spectrum of the rainbow. Pick your metaphor. God is the all of it, infinite and eternal.

If Levinas is right, if we encounter the infinite in the otherness of the face of the Other, the diversity of life forms on our planet are a sign, a divine revelation, an apocalypse. The awe and beauty that difference can inspire is a holy thing. We stand on holy ground.

If Swedenborg is right, this feature of life on our planet features on every level of reality, heaven itself is perfected the more diverse its inhabitants. We do not lose our identifying features, our differences, at death’s door. Our uniqueness is eternal in that sense also. We have in our Swedenborgian heritage a view of a heaven of infinite variety. Not even the angels can comprehend all the different ways love and wisdom can be expressed, Swedenborg suggests. Rather than being absorbed, or unified into some spirit or substance of sameness, we imagine a spiritual world where difference is a holy reality, and the harmonies it creates are unimaginably beautiful.

I’d like to conclude with some thoughts on how this relates to the churches and communities within our denomination. Many of us gathering here this week for the 198th Convention of the Swedenborgian Church of North America come with a bundle of concerns about the future of our various communities and organizations. This is a challenging time for any church, for reasons related to the pandemic, a growing cultural uneasiness around organized religion, or the distractions and business of modern life. Some of our churches struggle with building maintenance, burnout of leaders and core members, or other things. I know many of you share my deep affection for the churches in our organization, the people, the buildings, the traditions, and the sustaining teachings. It is easy to be fearful in the face of an uncertain future when you love something so much.

But I learned something important about loving a church when I was asked to be a part of the visioning process for the Garden Church at its inception. I remember distinctly the ways that Rev. Anna Woofenden, the church’s founder, wove in the idea of impermanence. This church would be temporary. It might last a year, it might last 500 years, but it would not be around forever. A garden is never a permanent thing. It is much easier to acknowledge the fleeting nature of a garden than a church building, so this was integrated into our conception of what this church would be. When the time came, it would be like compost, fertilizer for the next useful thing, but in a different form. To be sure, our intention was that it would grow roots and live a long useful life. But it would be temporary. I struggled with this idea, as someone with an affection, especially for stone churches, with their pretense of fixity, their iron gates, their organs that echo from generation to generation. A garden would have none of this. It would have plants that would grow and die, feed and be fed. People would come and go, too, some of them unrooted, unhoused, reminding us that we are all nomads, really. It would be a sanctuary to impermanence. But all of it would contain the infinite. All of it would participate in the eternal. It would be infinite and eternal, not because it would resist decay, but because it would be alive. And it is alive, eternal and infinite, like you and me.

The Garden Church reminds us that all our churches are gardens, and that all of us, individually are also churches and gardens. Temporary in one way, and eternal in another way. Dying and living. And it calls us to ask two questions: Where is your church most alive? This is where people will encounter the eternal. How does your church celebrate plurality or welcome and care for the stranger? This is where people will encounter the infinite.

Life and encounter, these are gifts we can cultivate, and tend like a vegetable patch. And we need reminding, always reminding, of what we have been told for over two thousand years “where two or three gather in my name, there I am in the midst” (Matt 18:20). Where two or three gather, there can be life and encounter. In these alone will we realize the promise expressed in Genesis 22, that we might multiply like the stars of heaven and like the sand on the shores of the seas. (Genesis 22:17).

Read the full issue of the July / August 2022 Messenger

View the entire Welcome, Opening Worship, and Keynote Address:

Meet Rebecca Esterson

Dr. Rebecca Esterson is the dean of the Center for Swedenborgian Studies at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California.