By Andrew Dodd

Last October (2022) was the 500th anniversary of Columbus

setting foot on land that, to most Europeans, was a “new world,” but in reality, it had been already been inhabited for many millennia by diverse people and civilizations, with languages and cultural practices that deeply connected all life rooted in their home on earth to the celestial and spiritual realms.

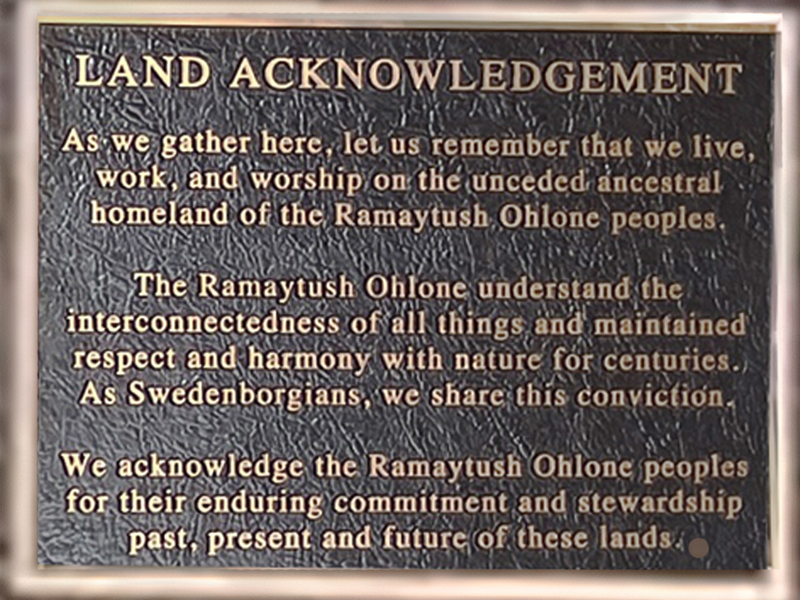

On Sunday, June 11,2023,the San Francisco Swedenborgian Church dedicated a new architectural feature at its entrance—a plaque acknowledging that the land it stands on is the unceded ancestral homeland of some of those people. It reads,

“As we gather here, let us remember that we live, work and worship on the unceded ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples. The Ramaytush Ohlone understand the interconnectedness of all things and maintained respect and harmony with nature for centuries. As Swedenborgians we share this conviction. We acknowledge the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples for their enduring commitment and stewardship past, present, and future of these lands.”

The dedication was streamed live on the church’s Facebook page as part of the regularly scheduled Sunday Service at 11:00 AM local time. (Link: https://tinyurl.com/SFSCnativeland)

At the start of the event, Senior Pastor Rev. Lee spoke about why we are doing this, as a reminder to us all, not only of the stewardship of the Ramaytush, but of our own stewardship of this land for the future as well. Council Secretary Laurie Carlson then read a statement of dedication about the debt we here owe the Ramaytush, and with some quotes from Swedenborg about the importance of our neighbors and the multiplicity of heaven. Peggy Magilen, the musician’s fiancée, then told an indigenous story of how, to native peoples the land is like their body, a whole person, in which all parts are needed. The indigenous musician — Blue, the last of the song keepers of his tribe—spoke his blessing, and played a sacred song on flute, “The Light Never Goes Out,” to conclude and solemnify the occasion. Finally, he placed his hand on the plaque in a gesture of acceptance and blessing.

Wherever you live in North America (and many other parts of the world) the land on which you live and work was originally inhabited by people who learned to thrive in balance with the resources of the land, to cherish and worship in that place, and bequeath the sacred connection with that land to their descendants, only to be driven from it by European newcomers who mostly considered them less than human, and the land as a commodity to master, to own, and exploit for profit.

As Swedenborgians dedicated to regeneration as our spiritual path, we owe it to ourselves and our communities to face up to, admit, and to repent the legacy of that sin upon which all of our material lives depend today. Think of The Lord’s Prayer. As descendants of those foreigners, and as a denomination founded and led by them, it is time for each of us to acknowledge the debt we owe to those original inhabitants and their descendants. Recognition and acknowledgement of our truths is essential to the first step of regeneration.

How did the San Francisco Swedenborgians come to acknowledge this? How did our process begin?

It began within an anniversary celebration of our church’s own founding on that very land. Many months of planning for two full weekends of planned events, speakers, engaging activities, and dramatizations planned for the 125th anniversary celebrations scheduled for March 2020—themed and titled Nature & Spirit—but was shut down by the recent pandemic just at the moment the celebration was scheduled to begin. Everything was cancelled. As the key organizer and promoter, having to inform the participants (some traveling thousands of miles), contributors, media, and the public at large that all events had been canceled was more than disappointing. But the health and safety of everyone was clearly the paramount concern. No one knew what was to come nor how long the cessation of normal life would last.

Adaptations had to be made to our Sunday Church services, moving to a live stream format on social media combining Reverend Lee’s service and live message in the church with prerecorded multi-media. Our music director, Jonathan Dimmock, innovated by recording the music for the services, even coordinating the contributions of our home-bound choir member’s vocal parts shared with me to merge into the live stream. Operations Manager Dana Owens and I collaborated on creating visual components for the choral audio. For our monthly Meditation Sunday Service, Jonathan suggested a musician acquaintance, the Native American flute player Blue, to play the music for that service. This could be done live in the church with the minister leading the service, the two of them keeping socially distanced. This effect on our services was very well received by those who attended online.

As familiarity with this worship format became routine, questions arose about reviving the Nature & Spirit symposium as an online event. In reformulating the anniversary for an online audience, I imagined music being an important aspect as it was in our online services. I included a classical guitarist playing a piece composed by a Japanese composer on Muir Woods National Monument. As a balance to Muir’s writings about indigenous people (misconstrued according to the Sierra Club) I thought of including a speaker on indigenous history and culture for a section themed on the roots of conflicts stemming from our lack of proper relation to nature, highlighting the correspondence of Nature & Spirit.

Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber, associate professor at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, suggested a local renowned indigenous leader to offer that perspective: Corinna Gould of the Lisjan-Ohlone village of Huichol across the bay in Oakland. Her presentation in the newly revived eight-part weekly series had a profound impact on those who watched, including on those in the church council. She graphically illustrated what life was like for the Ohlone all around the Bay Area, what an extensive network of interconnected tribes, their ancestors, and languages with similar rituals. There was a reverence for the plants, animals, and sacred places that made up their everyday lives. California, as a flourishing ecosystem of diverse climates and habitats for all manner of life, was an idyllic home to one of the largest concentrated populations of diverse indigenous people in North America. Corinna detailed how the lives of all the villages and the sophisticated political and cultural network of the California in general, and the bay region particularly, were quickly overturned when the Spanish missions were established, imposing an oppressive cultural and political regime that was diametrically opposed to the ways that enabled the tribes to flourish over thousands of years. Within a lifetime the newcomers who had preached to the original inhabitants of a loving God who urged love towards neighbors, changed to putting them in bondage for forced labor, banishing their customs, occupying their sacred places, looting their graves, chasing them from the resources they relied on to live. Eventually our own governing institutions treated them as an infestation to be exterminated in what’s come to be known as the California Genocide.

Now the survivors of this history are working to reawaken us, and each other, to their heritage and to those who have survived, how they are hopeful of reuniting and preserving what cultural heritage they can reclaim, and to establish respect and value for their people and their precious heritage and traditions. Part of Corinna’s address to us included suggestions of what we newcomers could do now to change our understanding of and relationship to the indigenous community. The first suggestion that had begun being implemented by cities and organizations was to publicly post and publicize a statement acknowledging the original inhabitants, their history and legacy, crediting them as caretakers of the land that our cities and businesses were occupying, whose few descendants are still living amongst us. The next step is to become allies in their efforts to reclaim with respect some revered space in our midst on which to revive cultural communities and practices to pass on that legacy, the life and memory of their people to the next seven generations. A simple and meaningful commitment to that alliance could be the regular contribution to local indigenous organizations of a “shuumi” or land tax, confirming the authentic intent of the land acknowledgement and making it material.

Since then, the topic of a statement of land acknowledgement repeatedly came up in our Stewardship Ministry and then in our Church Council discussions. A chord was struck, and a seed planted. We began to research what a land acknowledgement statement would sound like. We looked into who were the specific people that resided on the land of San Francisco where our church stands. Then we reached out to them and began a dialogue about their identity and history, the nature of our interest in them, our intent, our questions, and they guided Council Secretary Laurie Carlson on the wording of a land acknowledgement statement. She drafted and revised it, and the approved statement has been regularly included in our Sunday bulletin ever since.

Last year our church hosted the annual meeting of the Pacific Coast Association (PCA) of our denomination. Those of us involved in planning decided to develop its theme around acknowledging our debt to those who came before us, taking inspiration from Corinna’s powerful presentation, and with roots in The Lord’s Prayer’s request for forgiveness of our debts, and Swedenborg’s idea of spiritual regeneration. For the event theme’s title, I borrowed the original title from Corinna’s Nature & Spirit presentation “On Indigenous Land.” I added this Swedenborgian theme as subtitle: “Finding a Path to Regeneration,” suggesting a path forward, which can also reference our spiritual relation to each other and the natural world, recognizing God as source, and our responsibility to respect and care for that gift. Rev. Lee, reached out to Gregg Castro of the Salinan/Rumsien-Ramaytush, the cultural director of the tribe that inhabited San Francisco (who advised us on our land-acknowledgement statement) and engaged his participation in the PCA proceedings by offering a public presentation of local indigenous story. Gregg spoke very movingly and eloquently from his own personal and family history, a survivor’s legacy of his people being chased down, slaughtered, driven into hiding, the untold, unspeakably cruel past that no family wants to pass on to their children, and his journey of discovering his roots, his ancestors stories, sacred place names, social structures, and then deciding to accept the role of a cultural leader for his few surviving people. It was a very moving public event, well attended and received, attended largely by our neighbors and community members. So intrigued and moved was the audience that Gregg, very patiently, was answering questions long after the scheduled time.

Also, at the PCA meeting, Professor Zuber gave a presentation on the indigenous Sami people of northern Sweden, who for centuries were systematically treated with disdain, suffered dislocation, abuse, confinement, and reculturation efforts at the hands of the Swedish government, a cruelty known to Emanuel Swedenborg. Devin discovered that Swedenborg himself, had become familiar with the Sami, and at home regularly wore a traditional Sami cloak, presumably out of affection for them. Swedenborg, a privileged member of Sweden’s nobility, knew full well what his society was doing.

Imagine that your family now, or ancestors past, know the terror of oppression, of repeated cruelty and threats, constantly in fear of your life, a frightful escape seeking safety, or forced deportation tearing you suddenly from all you’ve known, or worse—witnessing the violent death of loved ones, the destruction of the land, community, all depend upon, and all that is your world by a powerful mob, army, or government—wouldn’t you want those who displaced your loved ones to at least acknowledge how their lives were made possible? Wouldn’t you want their descendants who flourished in your place and profited from that theft to know how their privilege was obtained? For those of us who came after, this is part of the foundation of our society, how our daily lives and communities are possible.

Many ethnic minorities living in America today experience threats and worse, yet they still come in hope of sanctuary, of survival, of a better life through whatever hardship awaits them here. But few experience the horrific legacy of genocide in their own lands as the first nations of the Americas. This is the legacy of America today.

An important point about pursuing an authentic act of indigenous acknowledgement is that it must begin with listening deeply, and with empathy, to the stories of those who do live with this history and its consequences, the circumstances that our neighbors live with every day. Acknowledgement is not an act of publicity, like an achievement to check off. To undertake the journey towards the acknowledgement of indigenous lands is to strive to love one’s neighbors as ourselves, to honor and respect their ancestors and descendants as we honor our own, and as they wish. When the act of acknowledgement is informed, sincere, and of practical use and service, then is the gesture meaningful and the act fruitful.

This past fall our church council proposed, and our members approved, a budget that included a monetary annual donation to the Ramaytush tribe as a token of respect and in acknowledgement of our debt for living and worshipping on the unceded land of these people.

Also, in the fall, due to the work of Corinna Gould and others, the City of Oakland returned approximately five acres of land owned by the city to Indigenous stewardship, a small but significant step toward healing. In November the Oakland City Council voted to grant a cultural conservation easement at Sequoia Point in Joaquin Miller Park to the non-profit, women led, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan Nation. The City granted the cultural conservation easement in perpetuity to the Land Trust, allowing them to immediately use the land for natural resource restoration, cultural practices, public education, and to plan for additional future uses, what any community in our country expects to be able to thrive as a community.

On this result Corinna remarked,

“This agreement with the City of Oakland will restore our access to this important area, allowing a return of our sacred relationship with our ancestral lands in the Oakland hills. The easement allows us to begin to heal the land and heal the scars that have been created by colonization for the next seven generations.”

Regeneration is a process that may take a lifetime, but the fruits it can bring inwardly through service to others is essential to our purpose in life, bringing us more aligned with heaven. Often it starts by listening with an open heart to the story of a stranger. Perhaps by creating a space to listen, even as small as a plaque, more of us can start our own regeneration. Let us dedicate the next 500 years to that process.

Here are some resource references to start your own journey with land acknowledgement and local indigenous tribes in your area:

Whose land you live on: interactive map

https://native-land.ca

Guides to Land Acknowledgement

https://usdac.us/nativeland/ • https://native-land.ca/resources/territory-acknowledgement/ • https://nativegov.org/news/a-guide-to-indigenous-land-acknowledgment • https://www.teenvogue.com/story/indigenous-land-acknowledgement-explained

Read the full issue of the Fall 2023 Messenger