By Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber

We often think of commencement as the end of something—often marking the conclusion of an academic school year, accompanied by a graduation. But etymologically, commencement is actually the beginning of something, with a great energy or force—the comm in “commencement” or to “commence” comes from a Latin root which means a strong force, and this lies behind our other English words related to power, like to commandeer and command.

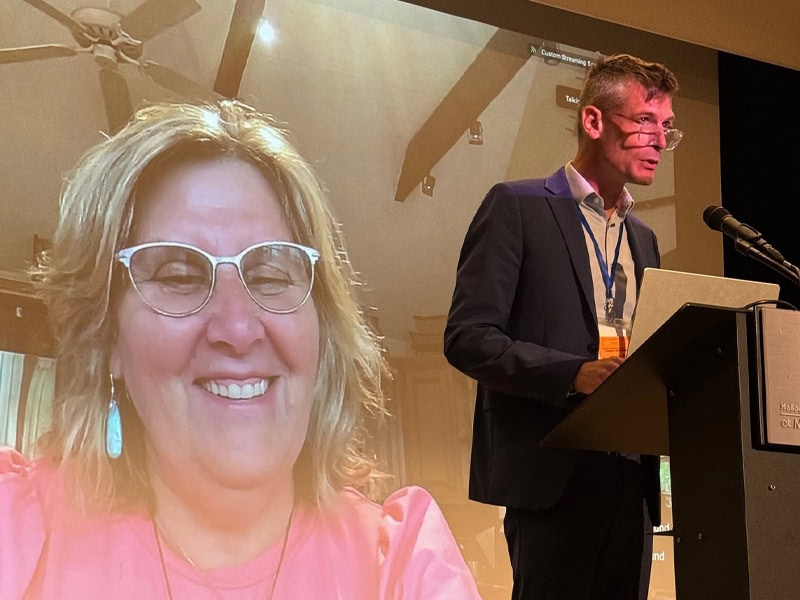

for the certificate in Swedenborgian Studies,

with graduate Lynn Chittick Thompson

on screen at the Kellogg Conference Center.

So for our graduates of our certificate program from the Center for Swedenborgian Studies, in Berkeley, California, the receiving of this diploma is a command of sorts, a powerful invitation to commence into the future with your training in Swedenborgian theology, to go out and engage with the world in all its complexity, beauty, and problems, with a mind and heart that have been shaped by your immersion in Swedenborgian thought, and its application to life. What a journey it has been! The great French poet Paul Valery (1871–1945) wrote that reading Swedenborg, for him, was like,

Pushing on into an enchanted forest where every step stirred ideas that flew up like unexpected birds, where shimmering hypotheses, echoes, and psychological chases ran together at every crossroad, and where the eye glimpses mysteriously renewed vistas, in the midst of which the hunter seeking rational answers gets encouraged, lost, and then he finds the track again, only to lose it from sight … I love the hunt for its own sake, and there are few hunts so captivating as this hunt for the mystery of Swedenborg.

So don’t feel discouraged, in other words, if you felt at times lost along the way; you are in good company with Paul Valery and so many others. In addition to the usual divinity school curriculum with its focus on the scriptures and biblical interpretation which many of our students must go through, the time you spent learning with us at the Center for Swedenborgian Studies has presented a mountain of seemingly insurmountable books: Swedenborg published eighteen different theological works in the second half of his life, and many of these were multi-volume, meaning that to get through them all in English, you’d have to read something like thirty-five books, some of them hundreds of pages in length, cover-to-cover. Tens and tens of thousands of pages, in the end—Swedenborg wrote so prolifically, as many of you know, that the massive archive of his manuscripts at the Royal Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, Sweden, constitutes one of the largest single-author manuscript collections from the eighteenth century in the world.

Thank goodness our spiritual tradition is not a competitive race requiring a marathon of reading! We hope in your journey at CSS, in addition to learning how to contextualize and wrestle with the unexpected birds and shimmering hypotheses in these voluminous theological works, that you have learned the application of the teachings, the insights, in your own life, grounded in love. The way to heaven is not by reading a set number of books, but by how you choose to live your life in relation to others. “A life without faith is like sunlight without warmth,” Swedenborg writes in the Arcana Coelestia, “the type of light that appears occurs in winter, when nothing grows and everything droops and dies. A life of faith rising out of love, on the contrary, is like light from the sun in spring, when everything grows and flourishes, and warmth from the sun is the fertile agent.” This metaphor about seasons—light and warmth, darkness and cold—is a powerful correspondence ever-present in the abundant earth we are gifted with; it is summer here in Michigan, with fragrant trees and flowers, the sounds of bird song in the mornings when we wake up in our dormitory or hotel here in East Lansing—and while a Certificate in Swedenborgian Studies is just, in the end, a little slip of paper, we hope it signifies your acquiring a kind of perception. That you have been given eyes to see, ears to hear, and even a tongue to taste, the lived goodness of a life of faith rising out of love, and that in whatever work you will continue doing or end up undertaking, that you will share this gift of perception with others around you.

But we can’t go into the future, commencing forth with this good news, without understanding the past that has brought us here. So, let us briefly go back in time, some two hundred and four years ago, to encounter some wisdom from one of our tradition’s ancestors, a moment that touches our own in more ways than one: a sort of Swedenborgian back-to-the-future. In 1821, a progenitor of our little tradition in North America, a man named Sampson Reed, was invited to give a commencement talk to the Harvard Divinity School. It was entitled “An Oration on Genius,” and among other things, it encouraged its listeners to cultivate inner spiritual perception, and to connect their regeneration inside their minds with the regeneration of the beautiful natural world and its cycles of life and birth, decay and death, fall into spring, summer into winter. In many ways this little talk could be said to be the first fully-fledged American Romantic manifesto; and by Romantic here, I don’t mean Valentine’s Day with chocolate and roses, but that tumultuous epoch of the early nineteenth century that produced poets like William Blake and William Wordsworth, and novels like Frankenstein. Sampson Reed, the Swedenborgian, ended his commencement address at Harvard by saying that “…living in a country whose peculiar characteristic is said to be a love of equal liberty, let it be written on our hearts, that the end of all education is a life of active usefulness.”

One of the young students listening to this talk was none other than Ralph Waldo Emerson, who would become the founding figure in the Transcendentalist movement, and a major philosopher and influence on American culture. Emerson was so struck by the independent Romantic manifesto vibe in Reed’s talk, that he later wrote it was as if Reed’s lips “mouthed words of fire.” Seventeen years later, Emerson himself was invited to give the commencement address at Harvard’s Divinity school on a hot July day, and his speech caused a scandal and sensation—don’t rely on books and learning, Emerson told the theological students, much to the shock and dismay of all the professors and faculty present; don’t worry about fitting into church traditions, all those good grades you got—pay attention instead to cultivating your inner spiritual perception and learning from the correspondences of nature that are always flowing around you. Emerson’s punk-style exhortation made him infamous, overnight, and it was deeply shaped his immersion in Swedenborg’s teachings. “In this refulgent summer,” Emerson said at the beginning of the commencement talk,

It is a luxury to draw the breath of life. The grass grows, the buds burst, the meadow is spotted with fire and gold in the tint of flowers. The air is full of birds, and sweet with the breath of the pine, the balm-of-Gilead, and the new hay. Night brings no gloom to the heart with its welcome shade. Through the transparent darkness the stars pour their spiritual rays down on us. We under them seem as young children, and this huge globe our toy. The cool night bathes the world as with a river and prepares our eyes again for the crimson dawn. The mystery of nature was never displayed more happily.

So, to our well-deserving graduates from our certificate program in Swedenborgian Studies, may you commence into the future with your training behind you and under your belts, prepared to meet the unfolding and flowing beauty of this earth which is ever-present around us!

Read the full issue of the Convention Special 2024 Messenger

Meet Devin Zuber

Instructor: Rev. Dr. Devin Zuber teaches at the Center for Swedenborgian Studies (CSS) in Berkeley, California, where he holds the George F. Dole Professorship chair in Swedenborgian Studies. He has lectured and published widely on how Swedenborg influenced the history of American environmental thought. An ordained minister (2023) in the Swedenborgian Church of North America, when he’s not reading or gardening, Rev. Zuber enjoys spending time on the California coast with his family (partner Suzanne, their two girls, and a floofy Goldendoodle named Louie).